For many, becoming a parent is one of the greatest moments of their lives. At Manchester Fertility, one of the UK's most established fertility clinics, we understand this better than most. For many of our patients, fertility treatments are their only chance to create the family they dream of. It is natural for those on their fertility journey to need advice and support as they navigate the process. And, although the road to starting a family has peaks and troughs for all those who walk it, for intended parents - who require surrogacy treatment to have a child with a genetic link to them - the journey can feel even more complex.

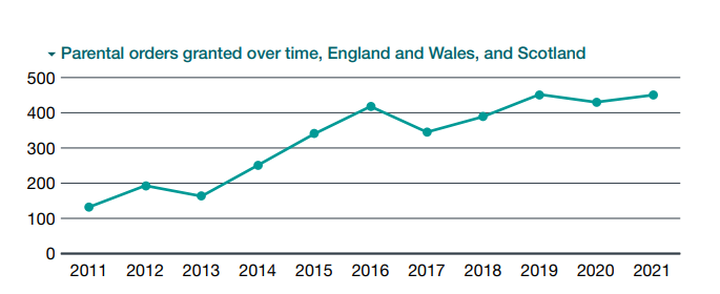

The Surrogacy Arrangements Act was introduced in 1985. Since then, society has changed, as have the needs of intended parents and surrogates. And, with the number of parental orders granted across the UK increasing from almost 200 in 2012 to 500 in 2019, 2020 and 2021 – the need to adapt and ensure the laws surrounding surrogacy are fair for both intended parents and surrogates alike is higher than ever.

Diagram taken from report published by the Law Commission for England and Wales, sourced here.

The Law Commission of England and Wales recently published its joint report with the Scottish Law Commission, outlining recommendations for a new system to govern surrogacy, which will work better for children, surrogates and intended parents and how that may affect the future landscape of surrogacy.

The report proposed a new system that would ensure that intended parents were the legal parents of their surrogate-conceived child at birth, as opposed to the surrogate, as is the current process.

What is a parental order?

A parental order is a court order which makes the intended parent or parents the legal parents of the child if one of the intended parents has been involved in the child's creation. This happens post-birth and removes parentage from the surrogate.

For those unfamiliar with the process, a parental order is necessary for all intended parents. A few parameters must be met for an intended parent(s) to apply for a parental order in the UK. These are:

- The intended parent(s) must be domiciled in the UK

- There has to be a medical reason for someone to undergo surrogacy – such as social infertility, in the case of male same-sex couples, where neither can carry a pregnancy, single men that cannot carry a pregnancy, or those diagnosed with infertility and/or are unable to carry a pregnancy

- There must be a genetic link to the child via one of the intended parent(s)

Currently, intended parents have to wait until the child has been born and then apply to the court to become the child's legal parents. The process can typically take six months to a year to complete. During that period, the surrogate is the child's legal parent, which doesn't reflect the reality of the surrogate-conceived child's family life and can affect the intended parents' ability to make decisions about the child in their care.

What changes to the parental order process does the draft bill propose?

Under the proposed pathway, intended parents can become the child's legal parents at birth. The new pathway will have eligibility conditions and introduce essential safeguards before conception so that regulation comes before, not after, the child's birth.

Instead of the complex and often stressful process of applying for a parental order through the courts, the new process will be overseen by non-profit making surrogacy organisations (called Regulated Surrogacy Organisations) regulated by the HFEA.

Are there surrogacy agreements that wouldn't follow the new pathway?

The surrogate will no longer be the surrogate-born child's legal parent in the new pathway.

However, if the surrogate chooses to withdraw consent before the birth of a child conceived through surrogacy, the surrogacy agreement would default to the original pathway, and the intended parent(s) of the child would need to apply for a parental order to gain legal parenthood.

This is only the case up until the child is born. Once the child is born, the intended parents would be the child's legal parents, and the surrogate would have a window of six weeks following the child's birth to withdraw her consent.

At this point, if the surrogate withdraws her consent and wishes to gain the legal parental status of a surrogate-born child, they would have to apply and have approved, a parental order as the intended parent(s) would be the legal parents of the child.

What happens next?

Building Families Through Surrogacy: A New Law is a report containing recommendations from a diverse range of people – with input from healthcare professionals, surrogacy law experts, fertility and surrogacy advocates and many more.

Since the publication of the report and accompanying draft bill, the Law Commission has released a statement describing their hopes:

"The new system would improve the current process, which involves a sometimes complex and lengthy journey through the courts after the child has been born, resulting in some couples waiting up to a year after birth before they become legal parents of the child."

The UK Government must now consider and respond to the Law Commission's recommendations. Those following the process should expect an interim response within six months of the publication of the report and a complete response within a year.

If the UK government accepts the recommendations, the draft bill can be introduced into Parliament to become law and change the landscape of surrogacy in the UK for the better.

As a progressive clinic with a diverse range of patients, many of whom are part of the LGBT+ community, we are exceptionally pleased to see surrogacy reform actively driven by the UK government. We are excited to see how, in the future, these reforms may help us support intended parents and surrogates on their individual journeys.

If you have any questions about the current surrogacy process or treatment, contact the clinic at 0161 300 2730 or online for more information. You can read a brief summary of the draft bill here.

Last updated: 9th May 2023